-

Michael Landy's Break Down: 20 Years

An Archive Display at Thomas Dane Gallery

13 April - 6 June 2021

-

Dr Stacy Boldrick reflects on the twentieth Anniversary

Break Down is sometimes referred to as a ‘lost’ artwork, as an event that took place in the past and can’t be remade, only remembered, as if the artwork is something separate from the things generated by its destruction.[1] And while it is true that Break Down existed for only two weeks, it is an artwork with a life both in its performance and in its aftermath. Break Down’s significance remains as an artwork that captured a national imagination, as complete media coverage in television, broadsheets and tabloids and personal responses from the public made clear at the time. The longevity of its impact is also demonstrated in its archive: its documentation, and the artworks and materials produced afterwards, along with the personal and collective memories of its audiences. Twenty years on, through a display of some of the materials in this archive, we look back at the performance in February 2001 and the work's significant and timely legacy.

-

MAKING IS BREAKING (1997—10-24 FEBRUARY 2001)

‘Break Down played on the idea of a psychological breakdown as well as physical break down. As a child I liked to take toys apart, that’s how I got to know how they worked in a way. Break Down is a grown up version of this.’ [2]

Taking objects apart to find out how they work is a logical and familiar physical response to understanding them. For scholars, the deliberate destruction of a beloved object as a response to its power can bring to mind Charles Baudelaire’s celebrated reference to the frustrated child who takes a toy apart and destroys it in the process of looking for, and failing to find their favourite toy’s ‘soul’, the thing that animates it and makes it powerful.[3] Baudelaire goes on to note that there is no ‘soul’, only a projection of self.

Dismantling objects in order to understand them is slightly different to the child’s quest for its toy’s soul. Curiosity about mechanical operations can actually lead to material knowledge, as opposed to a search for something immaterial which ends with nothing. From this perspective, taking a thing apart can be understood to increase the object’s value rather than diminishing or negating it. In Break Down, Michael Landy took apart his material life to forensically examine it.

Break Down was the result of four years of research and preparation, although its formal and conceptual roots can be seen in much earlier works. In the installations Market (1990) and Closing Down Sale (1992) Landy incorporated the furniture and atmosphere of consumer environments – the market stall and shopping trolleys – but he removed ‘desirable’ objects, undermining the cycle of consuming. The installation Scrapheap Services (1995), a fictitious cleaning company designed to dispose of ‘useless’ people in society, used the language of waste management systems to critique the application of economic values to human beings. In 1997, the sale of this work to Tate led Landy to question the value of his material possessions and newly felt financial security.

Drawings made focusing on the value of Landy’s material life first appeared in Michael Landy at Home (1999), an exhibition that introduced into the artist’s work his personal possessions and time-based performance. The exhibition took place at his home, where 17 drawings were displayed on walls made of custom-made Michael Landy-branded primary coloured milk crates while he was making the collage The Consuming Paradox (1999) over the course of the exhibition’s run. It was here that James Lingwood first proposed the idea of Break Down as a project with Artangel. Landy has described this exhibition as a conceptual and practical ‘launchpad’ for Break Down.

-

All of the components of Break Down were present in the exhibition Michael Landy at Home, 1998, with several drawings from it included in the current display. The exhibition presented the results of Landy’s research into material reclamation facilities (MRFs) and recycling more broadly, along with popular and academic writings on consumerism and ethical living. The artist was making the large-scale collage The Consuming Paradox on site. He brought together clippings of printed texts and images, handwritten notes and drawings as well as personal possessions and entire objects, such as pens made from recycled materials and magazines, books and videotapes including Material Recycling Handbook (‘acquired for free’), Consumerism – as a Way of Life, How Are We to Live? Ethics in an Age of Self-interest and Gustav Metzger: ‘damaged nature, auto-destructive art’. At the centre of the collage is a cut out drawing of key elements from a material reclamation facility: a conveyor belt, a raised platform, picking stations and sorters, along with bins for broken down materials. Conveyor belts and sorting stations also appear in the drawing The Subject of Consumption (1999). The two drawings Identification/Sorting/Separation (1998) and P.D.F. (Product, Disposal, Facility) (1998), explored this further, making the processes of the reclamation facility their main subject. Other drawings focused on Landy’s material possessions and their uses, with the words ‘LIFE’ and ‘style’ appearing in The Consuming Paradox, and in drawings such as Michael Landy’s Lifestyle (1997).

-

The Consuming Paradox, 1998 collage 182 x 244 cm.

The Consuming Paradox, 1998 collage 182 x 244 cm. -

With these drawings in mind, it’s not surprising that Break Down was originally entitled Michael Landy’s Lifestyle, and that its installation eventually featured a unique system based on the elements of a materials reclamation facility. The blue neon Michael Landy’s Lifestyle (1998) reminds us of the project’s origins. Landy planned to take everything – everything in his life, his ‘lifestyle’ – apart and back to their original materials to demonstrate the resources accumulated by one person (over 37 years) and the fate of those materials in the larger ‘waste stream’ when recycling options are limited. In the early stages of the project, the presentation was going to be a stationary tableaux, like Scrapheap Services (1995), perhaps in a disused warehouse, with material objects and remains displayed on shelves.[4] In time, Landy sourced the elements needed to make the installation take the form of a material reclamation system, and the closing down of the flagship C&A on Oxford Street provided the perfect site and context for the work. In opposition to its context, Break Down was an ‘anti-consumerist island’ in Oxford Street, performing consumption in reverse, not making things to sell and buy, but taking things apart and back to their original material states. Alignment with Oxford Street shopping was also part of this reversal: Break Down took place within standard shop opening times, even incorporating the extended hours of Late Night Thursdays.

-

Critical to the project was a systematic approach to disposal: an audit, an inventory cataloguing every single possession and an order to the process of taking each object apart. Landy and his friend Clive Lissaman separated all 7227 items into groups, and identified them by a letter and number: A for Artworks, C for Clothing, E for Electrical, F for Furniture, K for Kitchen, L for Leisure, P for Perishables, R for Reading, S for Studio (the contents of Landy’s studio) and MV for Motor Vehicle (a cherry-red Saab 900 16S Turbo). The inventory served to level the value of items, with all things broken down regardless of sentimental or monetary worth. This included artworks by Tracey Emin, Angus Fairhurst, Anya Gallacio, Gary Hume, Abigail Lane, Paul Noble, Chris Ofili, Simon Patterson, Jean Tinguely and Gillian Wearing, Landy’s own artworks, a Muji jumper, his father’s sheepskin coat, a bedside lamp, two Chubb keys, Grace Jones’s Warm Leatherette vinyl LP, holiday photographs, cat toys, cat food, a jar of Horlicks, Herbert Read’s A Concise History of Modern Sculpture, business cards, library cards, legal letters, love letters, Landy’s birth certificate and passport, a receipt for hat and gloves from the C&A closing down sale, screwdrivers, wall plugs, a hacksaw, drawings, Break Down sketch, 2001 (ink on paper), the Saab. The inventory’s concise, careful language makes it a valuable document of social history capturing an individual artist’s material life in 2001.

-

Yet Break Down’s 50,000 visitors did not spend most of their time sitting down and reading the inventory as a book. They experienced it as part of the performance, and the inventory as wallpaper within the C&A building. C&A’s remaining ‘Please Pay Here’ signs and mirrors framed the activity above and behind the installation: 12 operatives in blue boiler suits worked at different stations dismantling specific groups of items moving along rollers and a conveyor belt. (The Saab had a bay and a mechanic, Dave Nutt, to itself.[5]) A 100-metre long conveying structure snaked around the space in two figures of eight, its boiler-suit-blue base bearing bright yellow trays and their objects, that ascended to a sorting platform, where materials could be separated and tipped into a chute directing it to granulation. It took ten minutes for objects to travel round the conveyor belt. Amid notices stating ‘Providing Solutions to the Waste Handling Industry’, operatives dismantled each item with great care. This was not frenzied destruction, but an ordered, methodical series of acts as outlined in the project’s procedural guidelines. Although the space was filled with the cacophony of drills, saws and other electrical tools, some operatives were working in silence, reading letters, entering information into computers, sorting or labelling objects and administering the recording process.

Other sounds included music, as Landy’s vinyl record collection, CDs and cassette tapes were played throughout, with song lyrics particularly applicable to the experience. (‘Am I the happy loss?’ asked Echo and the Bunnymen’s song ‘The Cutter’.) Each day began with David Bowie’s ‘Breaking Glass’ and ended with Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’. As objects moved along the rollers, the levelling of their sentimental and economic values, the approach which gave everything the same value, slightly changed. Over the two weeks, certain items ended up having longer lives than others, and the record collection was among them. Some objects, such as the Saab, became surrogates of the self, and others surrogates of loved ones. The final object that was destroyed was Landy’s dad’s sheepskin coat.

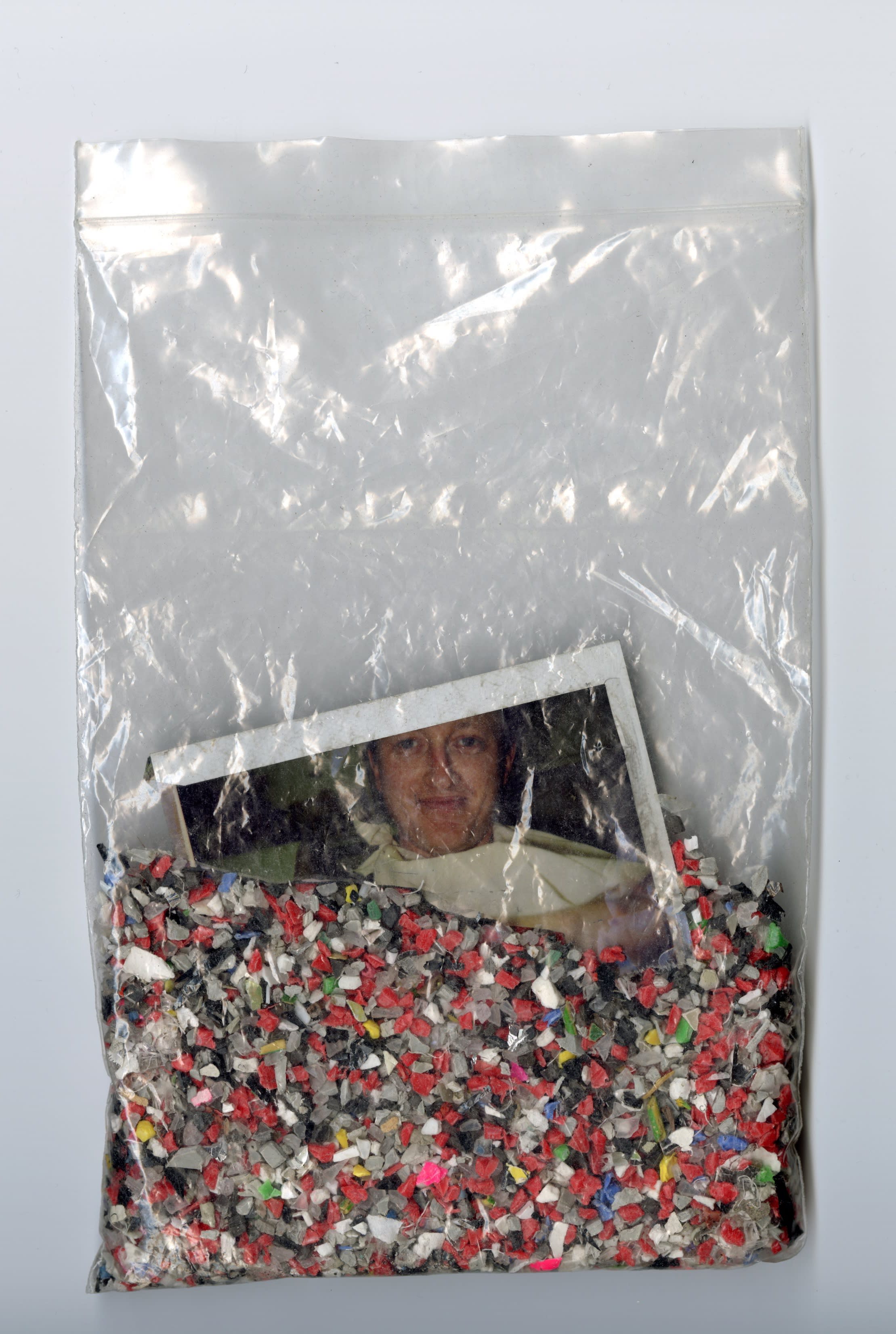

The remains of the materials from the shredded coat, and the other shredded or granulated 7226 objects were on display in front of the store windows to show the end results of the process.

-

Over the 14 days of Break Down’s existence, the media responded with a combination of outrage, vitriol and in some cases, humour and understanding. Richard Cork, writing for The Times (a sponsor), referred to the work as ‘a brutal end’, ‘alarming’, ‘an unimaginable sacrifice’, ’sinister’, and ‘blasphemous in its determination to question the new religion of rampant consumerism’. Headlines such as the Evening Standard’s ‘Madman at C&A’ aligned with the stereotype of the unthinking iconoclast and frenzied destruction, when the meticulous, methodical project couldn’t have been more different. Some critics chose to aestheticise it, and many focused on the most expensive items, the car and artworks, and other aspects of Landy’s personal life. Break Down challenged consumerism as an ideology and shed light on the environmental impact of the unlimited accumulation of material property.

In light of the heady state of consumer culture in 2001, stepping outside of the cycle of consumption as identity was difficult for many people to countenance, as was realising that not all things can be reused or recycled, and that landfill is a likely destination. But this was not the main response from viewers, many of whom questioned the centrality of their belongings to their lives for the first time, and what they valued most and why, engaging in discussions with operatives, invigilators and Landy himself (when not stationed at the elevated platform). This form of involvement of the audience in the work, and their participatory contribution to Break Down, was a response the artist never expected but greatly valued. As Landy has said, ‘It was literally those two weeks and what people took away from it that defined the artwork’.[7]

-

BREAKING IS MAKING (25 FEBRUARY 2001 – PRESENT)

In the last few days of Break Down, BBC4 started making ‘The Man Who Destroyed Everything’, charting Landy’s return to the material world. It starts with the artist requesting a new birth certificate, passport and keys, buying clothes and deodorant, and throwing away his blue boiler suit. It also focuses on his attitude to material loss and the impossibility of living without consuming and accumulating possessions. Near the end, Landy is filmed making an ethical consumer choice, an act that was less common then but has become mainstream now. It aired in 2002, as BBC4’s first televised programme, and simultaneously on BBC2.

Twenty years after it was made, Break Down lives on as a work that ‘confused people’s values systems’.[8] It cannot be remade, and cannot be exhibited in its original state, but it has been prolific in its self-destruction, especially in the digital era. What remains? In 2001, the actual remains were buried in a landfill site. (This may or may not be Mucking Nature Reserve in Essex, a former landfill site conserved and rewilded.) Other contemporary survivals include Artangel’s publications, an explanatory leaflet printed on yellow paper, and a book published in a ring binder format, along with other documentary material, including films and photographs.

The archival display at Thomas Dane shows how Break Down proliferated images from its first day onwards. The leaflet’s cover design featured Landy’s drawing of his car taken to pieces, and inside, smaller drawings of a packet of cigarettes, a pair of koala slippers, a Swiss army knife and a walking boot. The expandable Break Down catalogue included a fold-out image of a sketch of Break Down, along with a final supplemental chapter produced about the installation itself after the end of the performance.

-

While the iconography of material reclamation facilities and images of Landy’s personal possessions appeared before 2001, drawings made after Break Down, such as Compulsory Obsolescence (2002) and At a Routine Everyday Level, People Don't Feel the Need to Question the Validity of Consumerism as a Way of Life, the Dreams That are Engendered in Consumerism Give Meaning to People’s Lives (2002), brought in material from the public and published responses as well as some of the more personally significant items from the inventory, such as the sheepskin coat and references to the Saab. Collaged newspaper headlines and the Viz cartoon The Critics, advertising slogans and environmental mottos, sit alongside personal letters about the impact of the artwork from members of the public, all interwoven with notes about each item. Ephemeral materials informing the work such as notes from interviews with potential operatives, and a card sending ‘BREAKDOWN WISHES’ to the artist from all involved also sit within Landy’s handwritten remarks about them.

-

Newly discovered material also appears in the display. In March 2001, Wolfgang Tillmans gave Landy a set of 111 black and white and colour photographs of the performance as a memento in a presentation card box. They neither monumentalise nor sensationalise Break Down. In some photographs, Tillmans abstracts the work, capturing close ups of shredded and granulated materials, and in others he focuses on vistas of the installation space and its actions and elements, within which relationships and tensions between people and things play out.

-

Further afield, representations of Break Down have appeared in exhibitions in the form of the film and the inventory as wallpaper, as in the Hirshhorn’s Damage Control (2013). In 2012 the film and performance were part of a critical introduction to Destruction Workshops led by Landy and Lissaman as part of the Hayward Gallery’s Wide Open School. As more recent online public discussions about Break Down suggest, it remains a ‘live’ work in the public realm because the questions it asks continue to resonate with people.

Reviewing Break Down’s inventory now, one striking observation is the frequent listing of obsolete everyday materials. Outmoded formats such as image transparencies and slides, cassette tapes, faxes, and even letters and receipts might seem nostalgic to some. But how many of these items from 2001 would have survived until today? Appliances are designed to have shorter lifespans, with planned obsolescence in mind. The destination of so many personal possessions, after their recycling uses are exhausted, is, like Break Down’s 5.75 tonnes of remains, a landfill site. Plastic, once a wonder material, is now one of the most ecologically hazardous forms of waste.

Twenty years on, widespread recognition of the limitations of the earth’s resources and the climate emergency heighten the significance of Break Down as an artwork. Other aspects of everyday life are different too. Our digital lives have made a more minimalist material lifestyle much more feasible (although this has also led to its growth as an industry). After a year at home during a pandemic, many people may feel closer to their material possessions. Although ideas about ethical consumerism have been in existence since the 1960s with ‘Buy Nothing’ Days and publications like Ethical Consumer Magazine, today it is more widely practiced, and even fashionable. The principles guiding Michael Landy’s 2001 examination of his life are now shared by many.

After Break Down ended, Landy found himself unable to make new work for a year and drawn to thinking about ‘what makes us human’, and about what humans can offer to society beyond their economic worth. Eventually this led him to drawing weeds, plants that flourish without care and survive on nothing, for the series Nourishment (2002) and much later, he made Acts of Kindness (2011-12), an extended enquiry into the same questions. It is possible to see in Break Down’s archive, and the images and discussions the work produced, threads of these ideas about kindness and compassion in everyday human acts. While making Break Down, Landy felt the happiness of loss over the two weeks, liberated from his possessions as he and his team of operatives transformed them back into their original materials, as public interest and engagement surged. Although the artist has sometimes described Break Down as a work that was about getting rid of himself, as an experience, it energised him. In Landy’s words, Break Down was and still is ‘a celebration of life’.

Stacy Boldrick is Lecturer in Art Museum and Gallery Studies (School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester) and writes about contemporary and medieval art. Publications include Iconoclasm and the Museum (2020) and Iconoclasm: Contested Objects, Contested Terms (2007/2017; with Richard Clay). Curatorial collaborations include Art under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm (Tate Britain, 2013; with Tabitha Barber).

-

Click to watch

James Lingwood in conversation with Michael Landy

on the 20th anniversary of Break Down -

Archive material from the Thomas Dane Gallery archive, Artangel archive, and courtesy of Heather Ward and Tracey Ferguson.

With special thanks to the artists, Artangel, Stacy Boldrick and the contributions of operatives to our research.

DOWNLOAD ESSAY BY DR STACY BOLDRICK

DOWNLOAD LIST OF WORKS

MORE ABOUT MICHAEL LANDY

-

Michael Landy’s Break Down: 20 Years will be on display at Thomas Dane Gallery on the lower level gallery at No 3 Duke Street St James’s from 13 April.

For archive enquiries contact Georgia Spickett-Jones (georgia@thomasdane.com)

For exhibitions and sales enquiries contact Clare Morris (claremorris@thomasdane.com)

[1] Jennifer Mundy, Lost Art: Missing Artworks of the Twentieth Century (London: Tate Publishing, 2013), 243. ‘Break Down, 2001’, in Richard Flood, James Lingwood, Richard Shone, Rochelle Steiner, Michael Landy: Everything Must Go! (London: Ridinghouse, 2008), 113.

[2] Michael Landy, in ‘Michael Landy and Catherine Lampert, Out of Order’, in Andres Pardey (ed.), Michael Landy: Out of Order (Basel and Berlin: Museum Tinguely and Kehrer Verlag Heidelberg Berlin, 2016), 14-17, 15.

[3] David Hopkins, ‘The Surrealist Toy, or the Adventures of the Bilboquet’, Sculpture Journal, 28(2) (2019), 175-192, cites Charles Baudelaire: ‘Morale de Joujou’, first published in Le Monde littéraire, 17 April 1853; trans. Jonathan Mayne in Charles Baudelaire: The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays (New York: Da Capo, 1964), 202.

[4] Michael Landy in conversation with James Lingwood, 10 February 2021 https://www.youtube.com/watch?

v=0HuqtipWGWE&feature=youtu.be , (accessed February 2021). [5] Michael Landy in conversation with Dave Nutt, 20 February 2010, https://www.artangel.org.uk/

break-down/michael-landy-in- conversation-with-dave-nutt/, (accessed January 2021). [6] ‘A Conversation between Michael Landy and James Lingwood’, in Flood et al., Michael Landy: Everything Must Go!, 108.

[7] Landy in conversation with Lingwood, 2021.

[8] Landy, in Pardey, Michael Landy: Out of Order, 15.