-

SHADOWS

ELLA KRUGLYANSKAYA

-

There are women and there are women. There’s fruit and veg and there’s fruit and veg. There’s art and there’s art. There’s time and there’s time. Can you hear, see, feel the emphasis? Like that old joke of when the lyrics of the song are written out, so the joke doesn’t really work anymore, you say tomato and I say tomato, you say potato and I say potato. And no one really says pot-ah-to or to-mah-to anyway. Not where I am, at least. What I mean to say is that you might think you’re a side-step away, a different version of something, but maybe you are more like a shadow, an echo, an underside, a patina, a halo, the same word repeated so that it doesn’t sound different the second time, but becomes different by means of repetition, a kind of gathering force, a hint at the verso of life, the world just beneath (beyond?) this one.

-

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England -

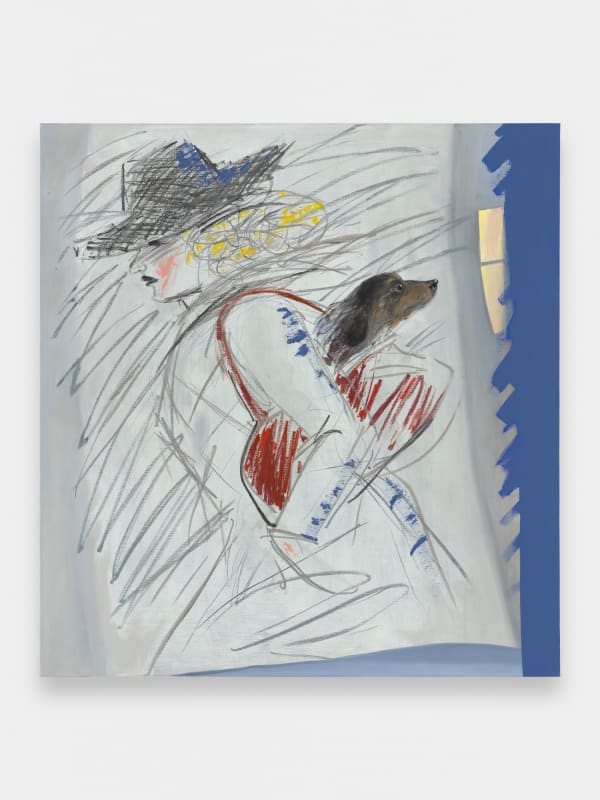

Ella Kruglyanskaya’s bright, lively, wry, self-aware canvases are filled with subtle questions about emphasis, which we might also think of as questions about reality, representation, narrative, and how far these tendencies in art fail when approached without question. (Or, perhaps as important, without humour.) To start with there are her women. Women rushing about town, wiener dog firmly lodged in a fashionable brown handbag. Women with legs crossed, waiting for the (rotary!) phone to ring. Women sketchily sketched, thick shadows falling across them, accentuating a flatness that reveals a picture plane within a picture plane: the women are not real, they are just (“just”) drawings, maybe tacked up on a studio wall, light flooding the room, the window mullions throwing angular shade, two worlds collide in one and then collide again, in slow-motion (stop motion, end scene, cut cut cut), here on the painted canvas.

-

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England -

Oh, but who (who!) said the women were real in the first place, rather than just (just) a series of lines converging to form a shape? They can, of course, be both, and often are, depending on who you ask. I like to think of these women — let’s say the blonde of Lilac Wine (2022), who is made of so many swirling lines that her odalisque, head towards us, bodily curves receding into the near distance, verges on abstraction — as possessed by a kind of internal poetry. I like to think of these women as not people, but words, phrases, ideas, affinities, feelings, images that stack up, and, of course, gestures, as in — an awkward wave, a haughty angle of the head, how my mother always pulls on her earrings to check the backs haven’t come off. You know, the things you do without thinking that would be on “character notes” if you were suddenly tasked with being not only you but another version of yourself as well, on a stage, or celluloid, maybe even in paint, what have you.

-

Lilac Wine, 2022oil on canvas99.1 x 79 cm.

Lilac Wine, 2022oil on canvas99.1 x 79 cm.

39 x 31 in. -

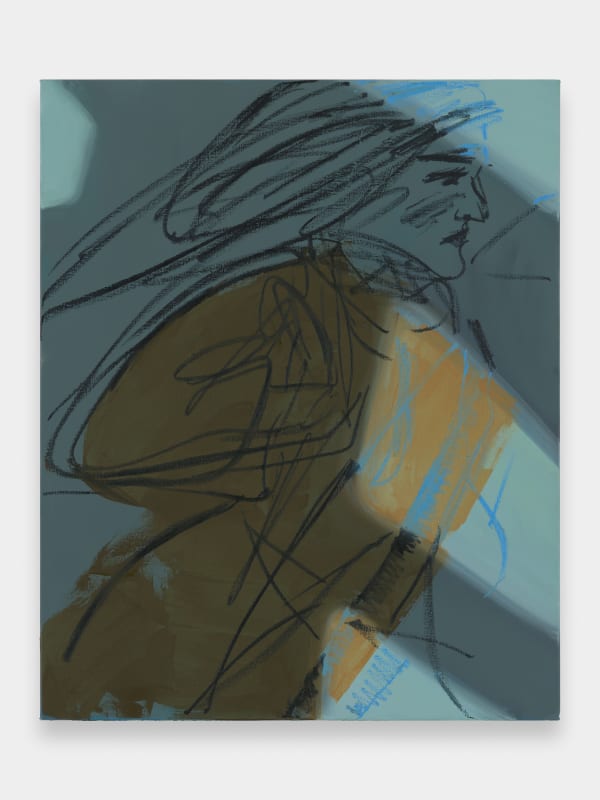

I like to think that the shady woman of Shadows (2022), in her mustard yellow ensemble highlighted with blue, her face cast in deep and otherworldly penumbra, has just left the sunny afternoon couch of her front room, where she forgot about time and had to all of a sudden throw down Frank O’Hara’s 1964 collection Lunch Poems (1964). She was perhaps reading, just up until that moment of departure, “Poem [Lana Turner has collapsed!]” and thinking how fine is the closing verse about what he thinks after seeing a headline on the street about the glamorous blonde of the Hollywood Golden Age, “LANA TURNER HAS COLLAPSED!” You see a woman, the idea of her, lines meeting on a page in words, ending with an exclamation, can stop you in your tracks like that. “I have been to lots of parties / and acted perfectly disgraceful / but I never actually collapsed / oh Lana Turner we love you get up.”

-

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England -

Does it matter what I like to think about these women? We are so embarrassed by narrative, by which I mean not humiliated but revealed. The human attempt to make sense. The human desire for familiarity, achieved by projection, empathy, imagination. As Joan Didion famously wrote, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.” But she didn’t mean it as a comment about the vitality of stories and writing, so much as their grasping, ameliorative qualities — how they make life bearable, create meaning where there is none. Our lady of Shadows, the Lilac Wine blonde, The Lady with the Dog (2024) in her fetching black hat, the monochrome woman of Adventure (In Gray) (2022) with her messy hair and blushing cheeks, are not people, they are paintings. What happens to them happens in paint, in the paintings, in the instant of beholding, in passing, on the way to the next and the next and the next painting, the exhibition is their environment, and we are caught in between them mid-stride, like a disjointed Muybridge elapse.

-

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England -

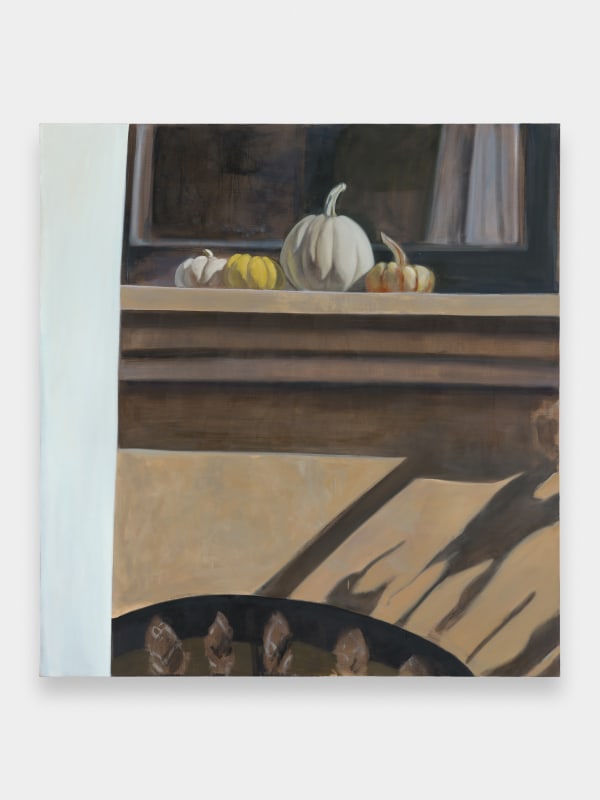

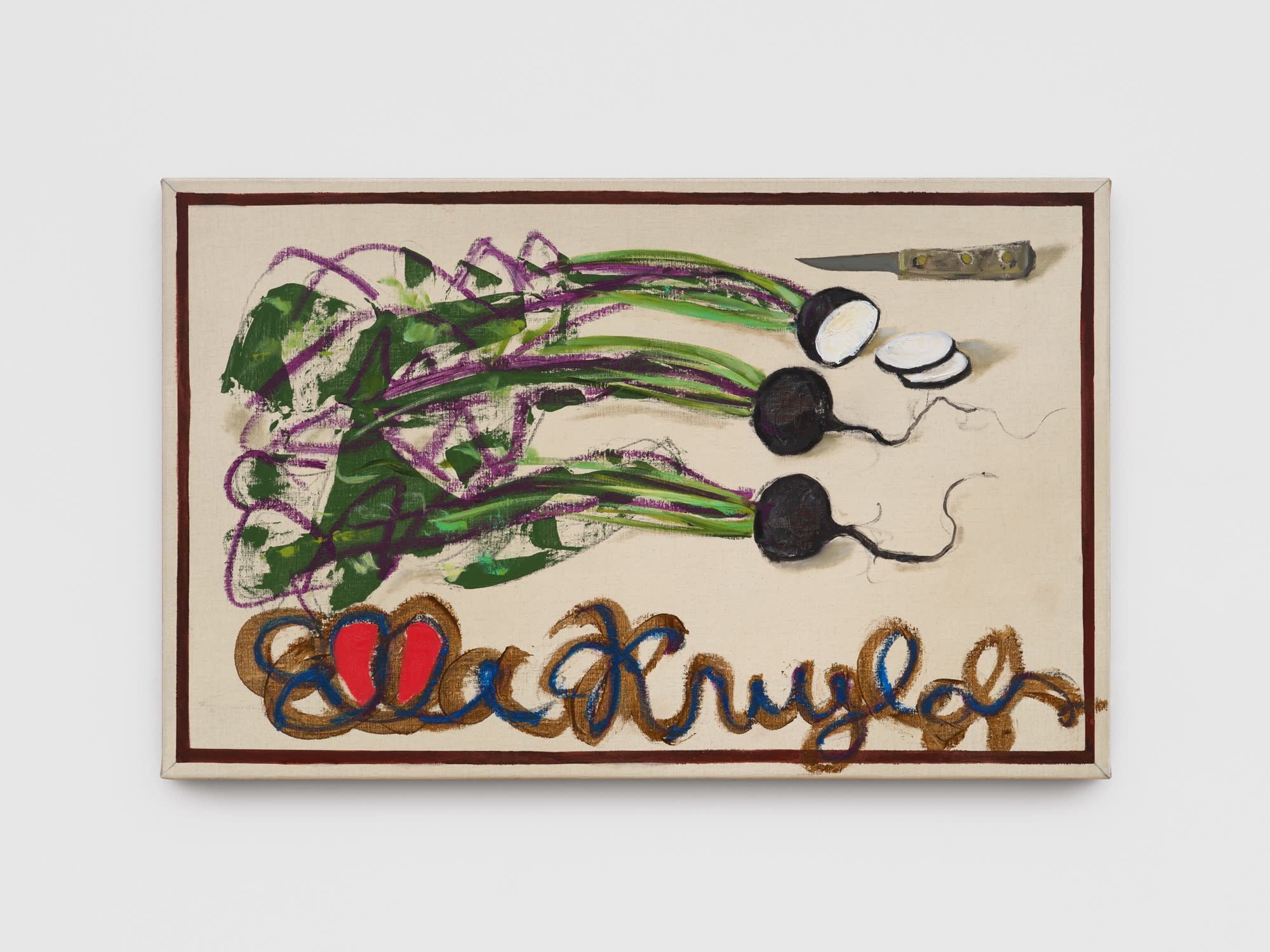

In some paintings they become art, as in capital A, Art, Historical, as if their own materiality has deformed the painted cosmos, twisted their visages, offered them sculptural boots for walking, erected austere tableaux, knocked them dead on the floor with aubergines, lemons, a red pepper curling like a scarf. Of course, every painting holds the past and present of its medium like a muscle memory, this is how we learn to see and make, an anxiety of influence. Kruglyanskaya wears her references lightly, with humour and easy facility. Her Radishes (2025) are exquisitely crosshatched, but she makes them a study within a study, a painted drawing taped to the painted wall; the ruddy fruit and wooden instrument of Odalisque with Lute and Apples (2024) are cool and precise, as in a Spanish Baroque still life, but the odalisque has strayed in from another era, her curves are Matisse-like, as is the blue of her outline, and her fuchsia body, well, it’s about to dissolve.

-

Lemondrama (After Manet), 2024oil on panel50.2 x 65.4 cm.

19 3/4 x 25 3/4 in. -

Melondrama (After Cotán), 2025oil on canvas157.5 x 167.6 cm.

62 x 66 in. -

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England -

This exhibition is called Shadows, and it is replete with them — dappled lights, strong angular swathes, delicate curves — but also echoes, shades, homages. We see hints of Manet, Magritte, Anthea Hamilton, Cotán, and in at least one work, Albers Variation (2024), work by the master of colour theory and hard-edge geometries is transformed into its opposite: messy figuration, loose and wild, no right angles, a woman sprung into motion, as if about to dart right off the canvas. But she is not a woman, she’s just (just) a painting, just like Albers’s squares and Magritte’s airless skies and Manet’s dead toreador and Cotán’s still lifes in alcoves against dark backgrounds. But in this world, we make our own sense, in whatever language is available. Calling something by its name, even signing it with one’s own, need not be indexical. In fact, a shadow — like a painting — never is.

By Emily LaBarge

-

Everyone and Their Mortality, 2024oil on canvas48.3 x 71.1 cm.

Everyone and Their Mortality, 2024oil on canvas48.3 x 71.1 cm.

19 x 28 in. -

Cut Roots with Signature, 2024oil on canvas48.3 x 76.6 cm.

Cut Roots with Signature, 2024oil on canvas48.3 x 76.6 cm.

19 x 30 1/4 in. -

Installation view: Shadows, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, England

-

For exhibition and sales enquiries please contact François Chantala: francois@thomasdanegallery.com and Phoebe Roberts: phoebe@thomasdanegallery.com

For press enquiries please contact Patrick Shier: patrick@thomasdanegallery.com