-

-

-

Thomas Dane Gallery is pleased to announce Father and Son, a solo exhibition of Akram Zaatari, opening in April 2024. The exhibition will be Zaatari’s third with the gallery and the artist’s first major solo exhibition in Italy.Akram Zaatari (b. 1966, Saida) has played a critical role in developing the formal, intellectual and institutional infrastructure of Beirut's contemporary art scene. He has produced more than fifty films and videos, a dozen books and countless installations of photographic material, all sharing an interest in writing histories and the search for records and objects, keeping track of their changing hands, the retrieval of narratives and missing links that have been hidden, misplaced, lost, found, buried or excavated. The act of digging itself has become emblematic of his practice while acting to restore connections lost over time, or due to war and displacement. Zaatari has dedicated a large volume of his work to the research and study of photographic practices in the Arab world and has made uncompromising contributions to the wider discourse on preservation and archival practice.

-

Rooted in his research practice, Zaatari’s exhibition in Naples retraces the element of restitution in the artist’s work, expressed mainly through text, documents and photographs, revisiting descriptions and recreating objects or ties that once existed but are now lost.

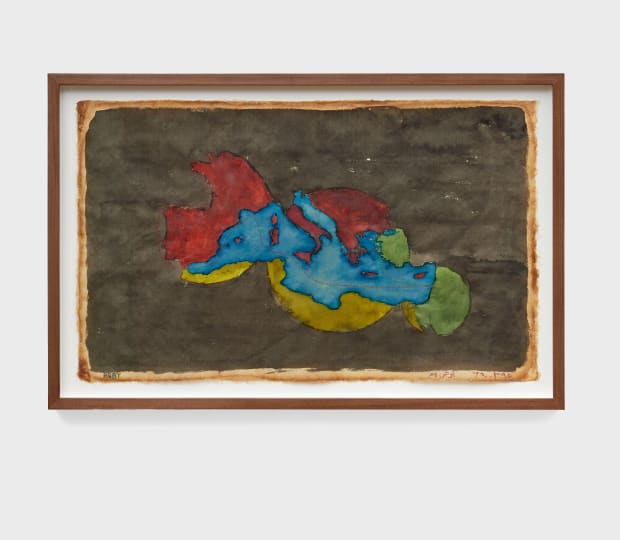

The exhibition features works across many media from the last two decades beginning with his two-hour-long video, Ain el Mir (2002), in which the artist looks for a buried letter that never reached its destination, through to Zaatari’s most recent body of work, Father and Son: A Mother’s Voice (2024) in which the two sarcophagi of two Phoenician Kings (father and son), separated since antiquity, are reunited metaphorically for the first time, and a series of new works on paper that look at the Mediterranean as a locus of exchange, extraction and movement across millennia.Amongst these works Archeology (2017), Photographic Currency (2019), Venus of Beirut, (2022) and most recently Ibrahim and Cat, For Inji Efflatoun (2024) which all engage in the process of recreating objects that have either vanished or were never produced. The brass relief Ibrahim and Cat gives new form to a photograph taken by the father of Egyptian artist Inji Efflatoun for his daughter to turn into a painting, which was never realized. This idea of ‘giving life to things that do not exist in the present’, as Zaatari describes, applies also to the recreation of a stone monolith that used to seal the King Tabnit’s tomb, completely destroyed whilst extracting the king’s sarcophagus in 1887. All that refuses to Vanish: The Tabnit Monolith, (2022) was made from drawings and notes left by Ottoman statesman and painter Osman Hamdi Bey during his excavation of the Sidon Necropolis. -

Father and Sonis the title of a performative gesture that once aimed to reunite the sarcophagi of King Tabnit, currently at the Istanbul museum and that of his son, King Eshmunazar II, currently at the Louvre museum in Paris. The two sarcophagi were originally brought from Egypt into Sidon before 500 BC, re-purposed by a Canaanite family of kings to bury its royalty. These are typical anthropoid sarcophagi from the late Egyptian period, sculpted in black Amphibolite stone under the XXVI dynasty in Egypt. Once in Sidon, the outer surface of the cover of Eshmunazor's sarcophagus had been shaved entirely, erasing what would have been normally a funerary text in ancient Egyptian, before it was re-inscribed with twenty-two lines in Phoenician. The ancient Egyptian inscription covering Tabnit's sarcophagus was found intact, but a short text in Phoenician was inscribed at the sarcophagus foot.

The two sarcophagi were discovered as a result of two distinct excavations led in different locations in Sidon, at two different dates. The excavations were separated by 32 years. They took place before and after the introduction of the Ottoman antiquity law of 1884. This is why the export of the sarcophagus of Eshmunazor II, found by Alfonse Durighello in 1855, was perfectly in line with the laws of its time. The sarcophagus of his father was found in 1887 inside a tomb discovered by a local mason named Muhamad al-Sharif (Mehmet Sherif), who had reported coming across archeological finds to the wilayet officials.

This is how Osman Hamdi Bey, artist and founder of Müze-i Humayun in Constantinople, came to Sidon with a mission to excavate and ship the finds. The unearthing of the sarcophagus of Tabnit has provided the world with important clues as to how Eshmunazor's sarcophagus might have looked like before it had been shaved.

Father and Son: A Mother's Voice brings together, metaphorically, the sarcophagi of father and son in a setup that narrates their current displays in Paris and Istanbul. The installation is a sort of an “informed object” that commemorates a mother’s attempt to inscribe herself into history, through the funerary text of her son and turns the perception father/son lineage into a trinity.

Moment 1

18.04.24

The title Father and Son brings up lineage, continuity, and male to male transfer of knowledge, heritage or power. It nevertheless implies the existence of a third figure crucial to reproduction; that of the mother, who was not mentioned in Tabnit's inscription, but who was highlighted in her son’s funerary text, which she might have entirely authored or commissioned herself. Emashtart, priestess of Astarte, must have played an important role in insuring that her husband and, later, her son were buried according to their wishes. But after them, she lost power and Bodashtart, Tabnit’s nephew, became king. The funerary text of Eshmunazor II proposes that she had played an increasingly influential role since the death of her husband including leading war and erecting a temple for the Canaanite divinity, Eshmun. The guess is that Emashtart was buried inside an incomplete black sarcophagus that was found, without any inscriptions, in the same hypogeum as Tabnit’s tomb.

This first phase of installation is a representation of the sarcophagus of Eshmunazor II, inspired from its 1997 display, standing at the Crypte Marengo, at the Louvre Museum, 3212 km away from Sidon. It is represented schematically highlighting the scratch at the lower eyelid, which makes the facial expression carved into black rock look like crying while the important inscription in Phoenician is displaced, mirror-imaged, into its shadow. A mirror, cut in the shape of the silhouette of Eshmunazor’s sarcophagus shows an ultrasound backlit image in its centre, making sarcophagus look like carrying a human fetus. The mirror helps also reading properly the Phoenician script built into the shadow.

Moment 2

20.05.24

The second moment of this installation celebrates the finding of the sarcophagus of King Tabnit thirty-two years following the finding of that of his son. The sarcophagus is on display today at the Istanbul Museum, lying down horizontally, 969 km away from Sidon. Its installation thirty-two days following (moment 1) points, schematically, at the passage of thirty-two years. Tabnit is represented in as a bas relief, lying horizontally on the floor behind the sarcophagus of his son, in such a way that the two cast a single shadow, with the Phoenician inscriptions found on both sarcophagi. Given their presences in two national museums that inherited a lot of the frictions between France and the Ottoman empire, namely the Louvre and Istanbul Museums, this specific installation of the two sarcophagi is an attempt to overcome their impossible reunion in real. The two sarcophagi are here united through a single shadow that fuses them in an imagined space, in which the mother has a place so that the whole is perceived as a trinity.

-

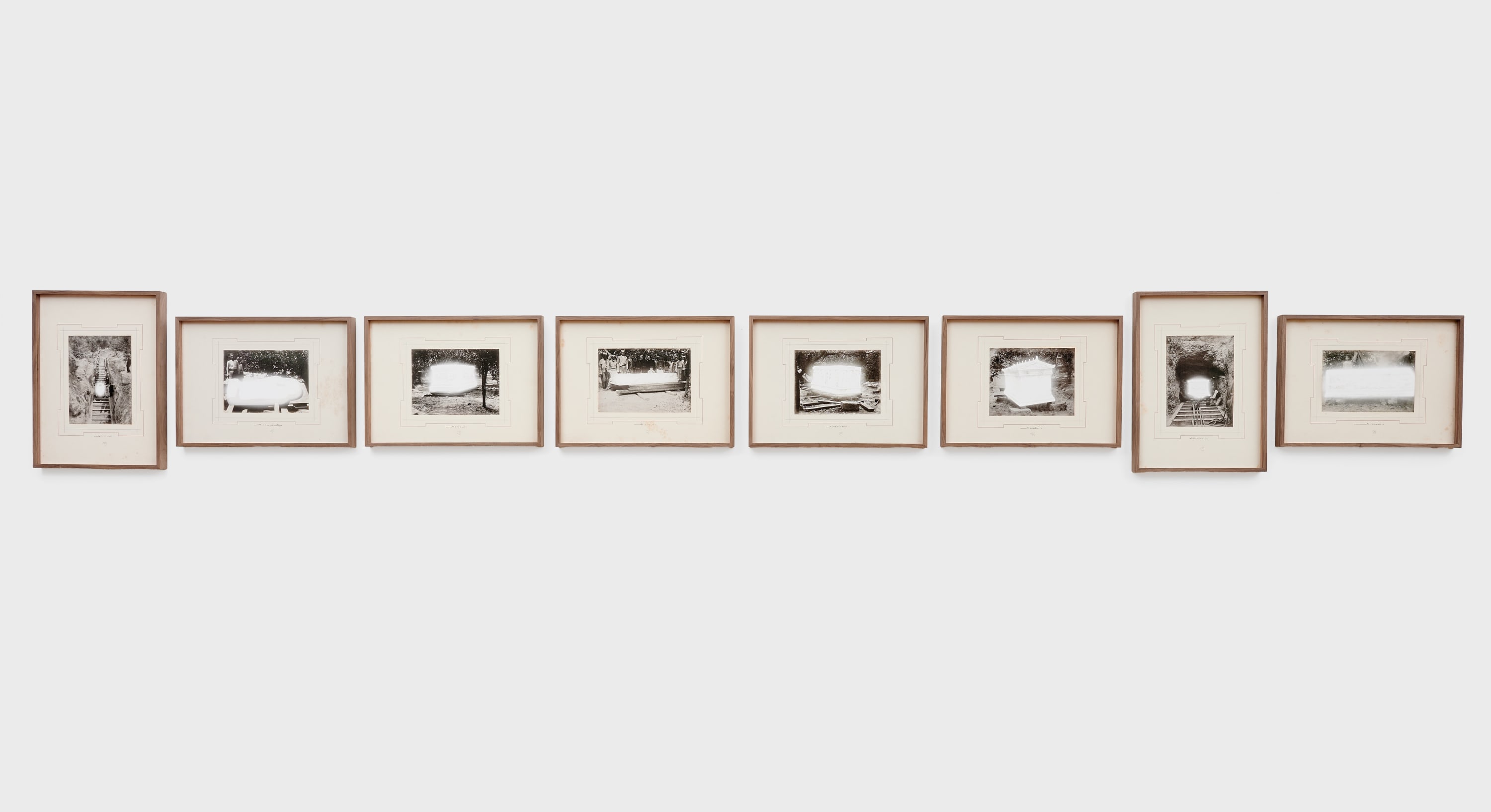

An Extraordinary Event, 2018

inkjet print, in 8 parts

44.6 x 35.7 x 3.5 cm.

17 1/2 x 140 1/2 x 1 ½ in.

Photographs are based on Abdul-Hamid Album #91533. Courtesy of Rare Books Library, Istanbul University.

-

-

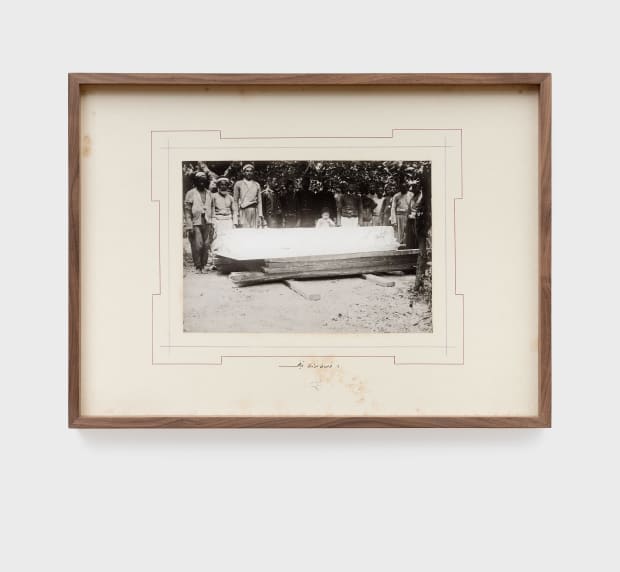

I, Tabnit, 2024

inkjet print, acrylic

52 x 74 cm.

20 1/2 x 29 1/4 in.

Photograph based on Abdul-Hamid Album #91533.

Courtesy of Rare Books Library, Istanbul University.

-

All that Refuses to Vanish: The Tabnit Monolith, 2022

3D-Routed hand-polished Spuma Limestone, Bchaaleh, North Lebanon, rope, crane

300 x 216 x 153 cm.

Stone dimensions: 34 x 69 x 32 cm

-

Above and Below, 2024

porcelain tiles, in 2 parts

80 x 40 cm.

31 1/2 x 15 3/4 in.

-

Ain El-Mir, 23.11.2002, 2002

Video, mono sound

154 minute

-

Archeology, 2017

Pigment inkjet print on gelatin treated glass, acrylic medium and sand

Floor standing preservation flood light

210 x 317 x 115 cm.

82 3/4 x 124 3/4 x 45 1/4 in.

Photograph courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation

-

-

-

Ibrahim and Cat for Inji Efflatoun, 2024

brass

26 x 28 x 1.5 cm.

10 1/4 x 11 x 1/2 in. -

-

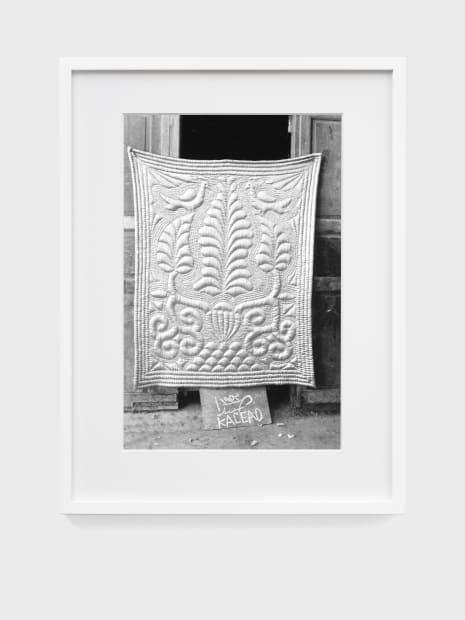

The Fold, 2018

8 stories and 8 photographs.

photographic prints, text, overhead projector, dimensions variable

-

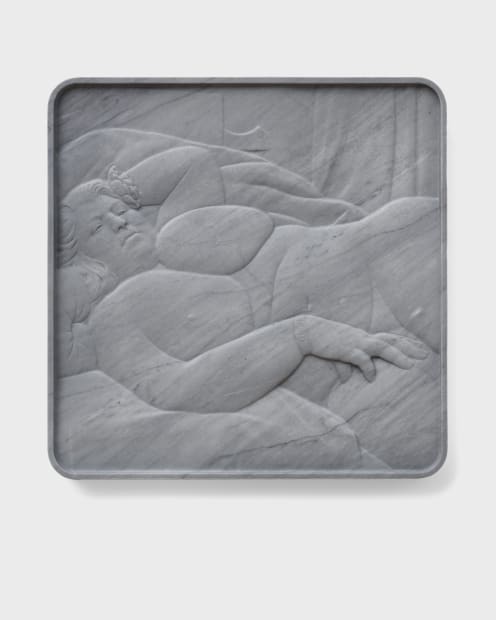

Venus of Beirut, 2022

3D routed, hand-polished Grey Bardiglio imperial

50.5 x 50.5 x 4 cm.

20 x 20 x 1 1/2 in.

-

[ʾRṢ YM] Sea Land, 2024

ink and cotton thread on mulberry paper

36.6 x 60 cm.

14 1/2 x 23 1/2 in. -

-

-

For exhibition and sales enquiries please contact Clare Morris: clare@thomasdanegallery.com

For press enquiries please contact Patrick Shier: patrick@thomasdanegallery.com